The Tree of Jaccard

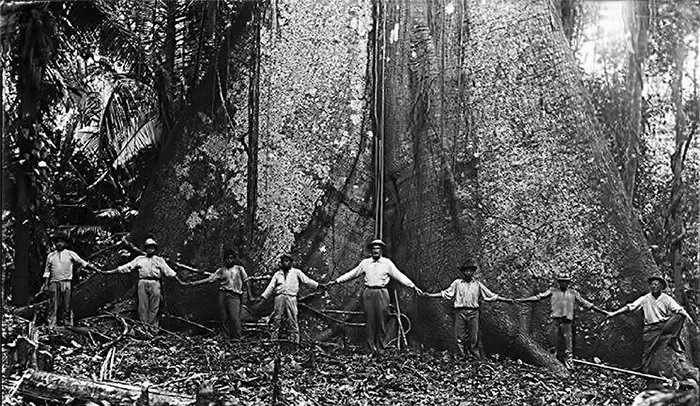

In 1965, a group of loggers ventured deep into the Chiquibul forest in Central America.

They happened upon an absolutely massive tree.

The men weren't prepared for such a gigantic find and had only axes at their disposal. But shooters shoot, and loggers log. They got to logging.

Over the course of weeks, laboring in the sweltering rainforest, the band of loggers chipped away. Finally, the tree fell.

But lacking sophisticated equipment, the loggers had miscalculated.

Instead of falling onto the forest floor, the tree toppled backward into a ravine; it was now impossible for the loggers to retrieve it.

It stayed in the ravine for over a decade, becoming a tale for travelers—the massive mahogany tree trapped deep in the jungle.

One of those travelers was an American wood importer named Robert Novak. Novak was intrigued. He waited out a month of heavy rain and then trekked into the rainforest.

The trip was worth it.

Upon inspecting the tree, Novak was captivated by its "rich, wavy figuring."

"Lying in that jungle ravine in the era of rugged Indiana Jones explorers and Jimmy Buffet pirates, Novak saw 13,000 feet of virgin lumber—and dollar signs. “I knew I could sell it,” he says, “but not because it was mahogany—you couldn’t really make much money selling mahogany unless you were dealing with millions of feet. What I made my money on was the unusual qualities of wood. Like everybody else, I was attracted by this tree’s quilted quality.”

The wood was strikingly beautiful and, somehow, it had not rotted.

Novak and his crew began the gargantuan task of cutting the tree into 13-foot pieces and loading them onto trucks. Next, they trucked the wood 100 miles to the Chiquibul River before floating it another 70 miles downstream to an old sawmill, where it was processed into boards.

Novak then began the work of importing the wood back to the United States and finding a market for it.

The mahogany's distinctive quilted pattern first caught the the of furniture makers and craftsmen, who used it to create high-end statement pieces.

But then, in the late 1980s, guitar makers began working with the wood.

It turns out the tree didn't just look beautiful—it sounded beautiful.

This is when the tree became The Tree.

Although not normally a fan of mahogany tonewood, The Tree found another admirer in master inlay artist, and guitar maker, Harvey Leach. "I was immediately stunned by its beauty...and it sounded magical," Leach said. Tonally speaking, it was "nothing like mahogany but more like the very best [Brazilian] rosewood, with this astonishing clarity and bass response."

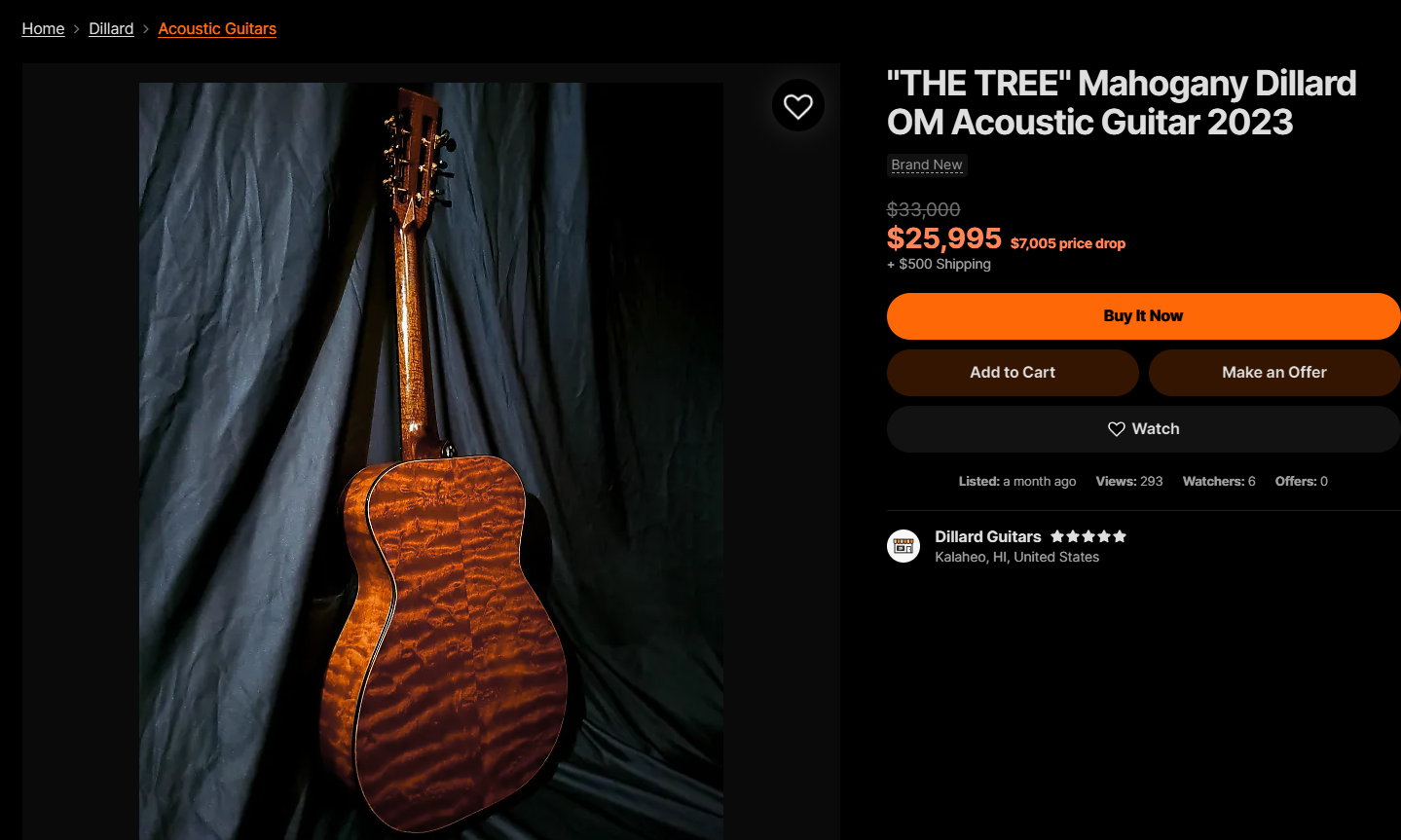

Today, The Tree is some of the most sought-after tonewood in the world... in part because it appears to be one of a kind.

The Tree's distinctive properties are probably the result of a genetic abnormality. But whatever the cause—the particular type of mahogany harvested from The Tree is likely all that will ever exist.

Fortunately, The Tree was so massive that even decades later... some unused wood remains.

Of course, buying a guitar made from The Tree is a major expenditure... even if you find one on sale.

Robert Novak—the true Bobby Trees—found a jungle ravine log.

It turned out to be the most valuable tonewood on earth.

Talk about a late-round gem.

That's at least twice as cool as hitting on Kyren Williams last year. Maybe even three times as cool.

This Feels Suspiciously Like a Metaphor

Let's imagine we've entered a guitar-making competition.

This is a very strange competition. Competitors must complete their guitars in the summer, but they aren't judged until the final day of the year.

In the meantime, the competing guitars are handled by a notoriously unreliable shipping company with a track record of mishandling, misdelivering, and straight-up breaking guitars in their possession. They get especially careless in late December. It's entirely possible the best guitar doesn't even make it to the judges overseeing the final.

Oh, and the judges. No one knows who they are or what exactly they're looking for. A great guitar, for sure. But the judges are going to have hundreds of great guitars to choose from. What separates the winning entry will be how its individual components work together in some unspecified way during one afternoon half a year from now.

There are so many variables to consider, and even little things can make a huge difference. After all, wood is sensitive to humidity; even the weather could come into play. Someone should check if it's an El Niño year.

But you're feeling good. You're a strong luthier, and you love making guitars. And crucially, you have a major material edge.

You found another Tree.

Even still, simply having some sweet mahogany won't win us the competition. For one thing, we don't have an unlimited supply.

Although you were much quicker to identify the next Tree than our guitar-making competition, word eventually got out.

We were only able to secure enough wood from The Tree to make 50 guitars, 30% of the 150 we plan to enter. Still, that gives us a sizeable advantage over the average luthier, who will have roughly an 8% share of Tree guitars.

But there's another issue. The Tree's magical tonal properties are related to its dense character. It's a rigid wood best suited for the back and sides of a guitar. We'll need to settle on a different wood for the top—an essential pairing. We'll also need to decide on the bracing materials and pattern. Then, we need to nail down details for the binding, bridge, saddle, soundhole, scale, neck, fretboard, nut, headstock, inlays, tuners, string spacing, string type, and setup.

The Tree provides a big edge but we still have, let's say... 17 other decisions to make.

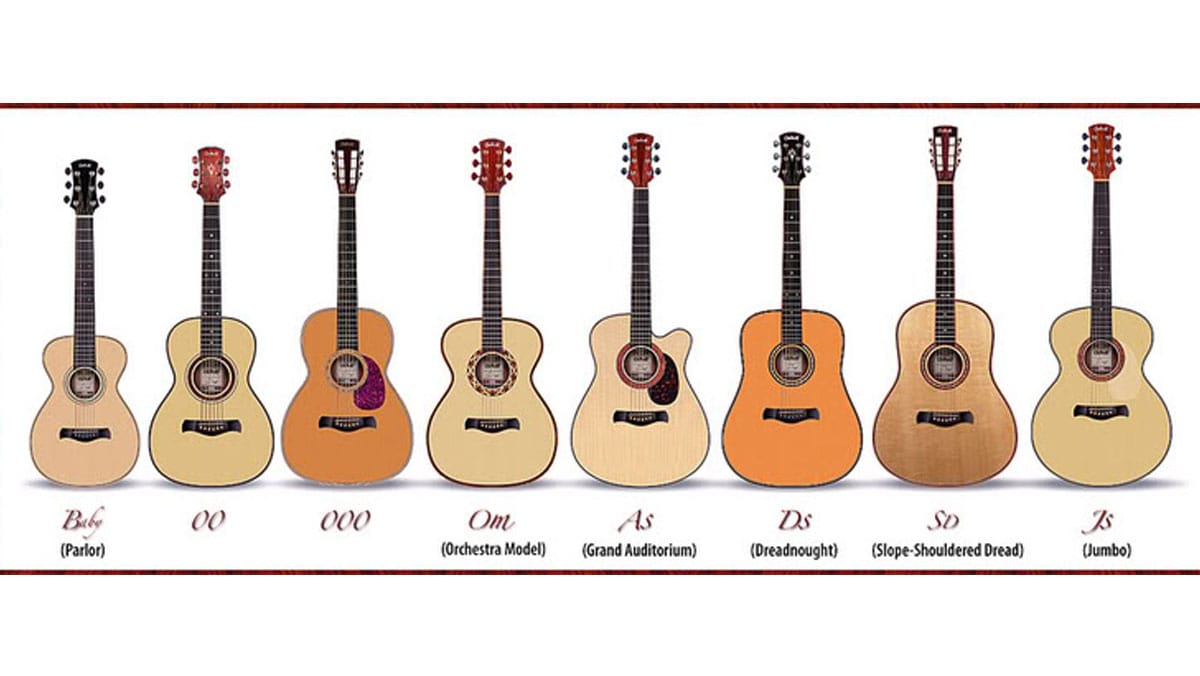

And we haven't even talked about structure. What types of guitars are we building? Do we want robust Slope-Shouldered Dreads or trendy 00 builds?

Maximizing An Edge

We have a lot of decisions to make in this guitar competition, but let's not lose sight of what our edge is.

30% of our guitars are guaranteed to have the best back and sides on the planet. But what's our next move? That depends on how confident we are in selecting the right materials and builds to pair with The Tree.

Unfortunately, we cannot be nearly as confident in our non-Tree materials or build selections. You have some strong leans, as do I. But we also know we're going to be wrong on some of those medium-confidence stances.

For example, for some reason, I thought last year's judges would absolutely love Buckeye binding. In retrospect, I probably got carried away with that mostly decorative addition. Sorry about that.

Still, we're not blindly guessing in the dark. We're damn good luthiers! And this is a big competition with lots of entries. We can't sit back and hope our one edge wins it... we're not even the only one with that edge. Other people found The Tree, too, remember?

Certainly, it makes sense to pair our Tree guitars with our strongest leans at a higher rate. However, we need to be intentional and thoughtful about those pairings and reevaluate them at various points along the way. We can't get carried away with how much we press secondary edges.

It's always tempting to make the selection you feel best about at every turn, at every available opportunity. But we should also consider that those preferences are often subtle and narrow. And if we're betting strongly on something that we don't feel that strongly about, pairing that new stance with our strongest edge doesn't press our advantage. It actually undermines it.

Again, we have enough wood from The Tree to build 50 guitars—a massive edge. But we don't know for sure what else the judges will be looking for. Therefore, making these 50 guitars extrememly similar to one another will likely prove to be a catastrophic missed opportunity.

The only real reason to do that would be if we had as much confidence in our other materials and builds as we do in the rarest tonewood available. And even if we have that confidence... it is probably hubris. There are only so many ultra-rare finds in the world. What are the odds we will find a handful or more in the same summer?

Rather than hitting that multi-leg parlay, it's more likely we find ourselves wondering why we repeatedly combined Bateman Spruce with The Tree when we valued Rachaad White Maple and Pacheco Cedar only slightly less... but rarely paired them with our biggest edge.

Ultimately, yes, we are trying to build exceptional guitars. But we also want these guitars to be distinct from one another. Otherwise, our bet shifts from our actual advantage – The Tree – to a multi-leg parlay slip that has far lower odds of hitting.

Jaccard Similarity

We're not luthiers, obviously. We're best ball players. And as best ball players... we don't actually know if we've found The Tree until well after we've committed to our building blocks.

For us, identifying The Tree in the first place will come with some false starts and may ultimately end in failure. Your May belief that a player is The Tree isn't an excuse to double down in spite of July evidence that undercuts the thesis of the play. Sometimes, a tree lodged in a jungle ravine isn't a once-in-a-lifetime discovery; more likely, it's a rotting log.

If you're willing to bet ~30% of your portfolio on a player... he should probably have some truly rare, Tree-like qualities. Otherwise, take him less frequently and focus on sound roster construction with a strong understanding of draft capital allocation.

The LegUp Best Ball Rankings will help you find stands worth taking. But massive player stands are not required.

In fact, if you're excellent at roster construction... that might be your biggest edge. Forcing player stands could undermine your roster construction edge in the same way that ill-advised player combos can undercut a target-player hit.

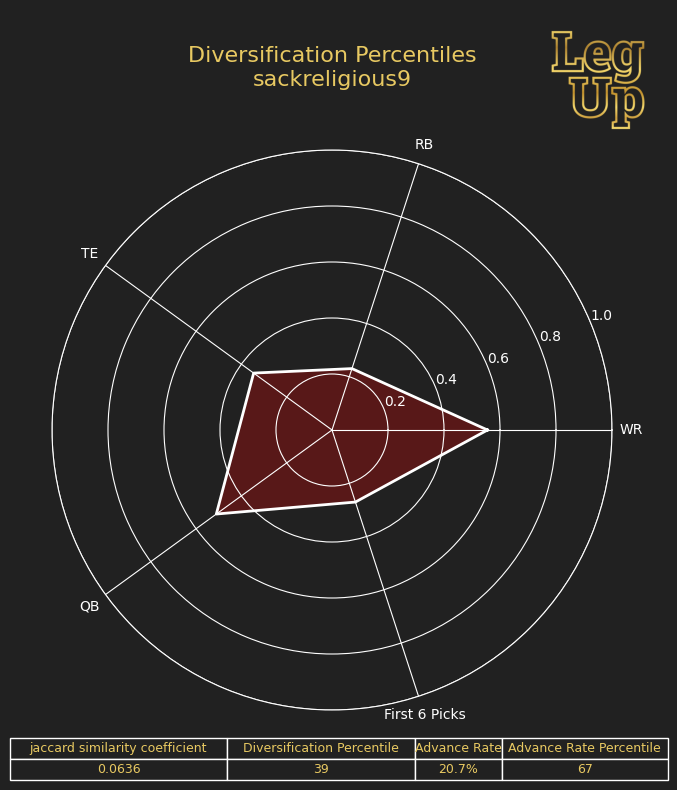

Per Sackreligious, drafters who max entered BBM4 in a diversified way did quite well.

"Of the 100 most diversified drafters, 15% of them had below a 20th percentile advance rate, while 13% of them had above an 80th percentile advance rate. The average advance rate for the 100 most diversified drafters was 18.7% or about 112% of the neutral advance rate. And the most diversified drafters' advance rate was 128% of the 100 least diversified drafters'."

Although big player stands aren't a necessity, I do view them as a potential edge.

Personally, I think they offer a big potential edge in a format that heavily rewards late-season production with an ADP environment that hasn't fully priced that in. If I'm taking a massive stand on a player, I don't just want him to be a great value at cost. Ideally, he should profile as a player who will peak at the end of the season.

At the same time, I've been working for years to dial in my player stands to boost the payoff when I'm right. And I do literally mean years.

This episode of Establish the Edge from 2020 touches on this same concept... how do we press an advantage without undermining ourselves with overconfidence?

Really wish I didn't tout Jalen Reagor's year 2 potential in this episode.

2023 Diversification Percentiles

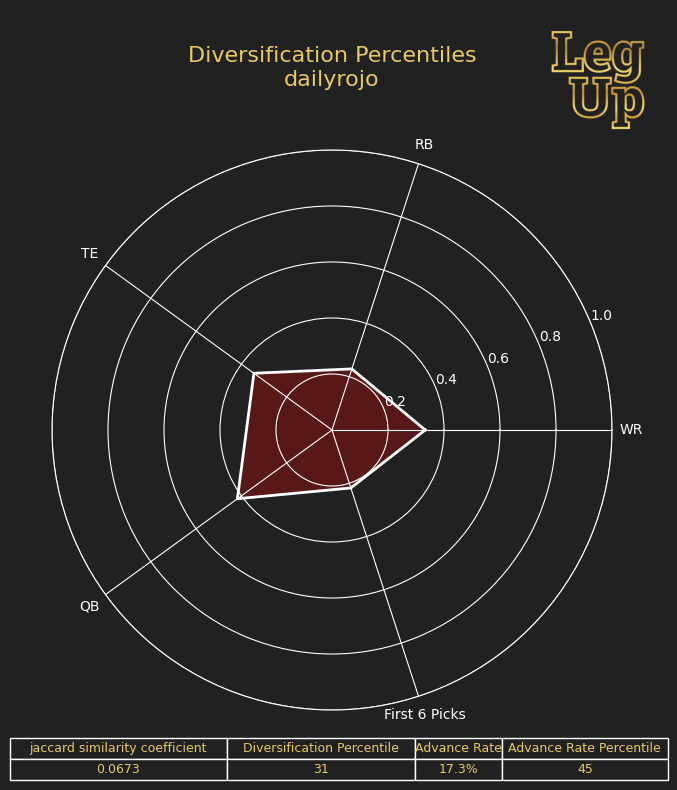

Ultimately, I feel good-not-great about my 2023 play from a Jaccard similarity lens.

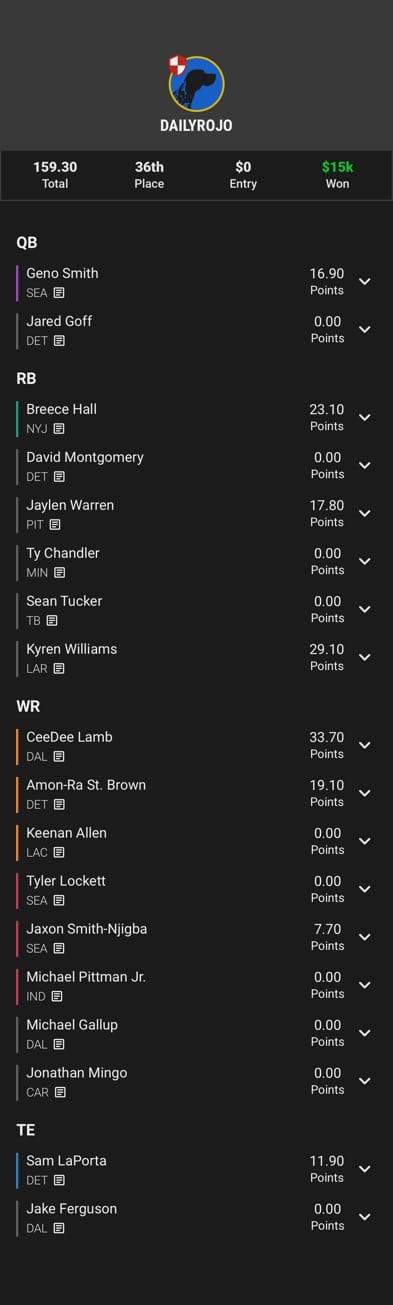

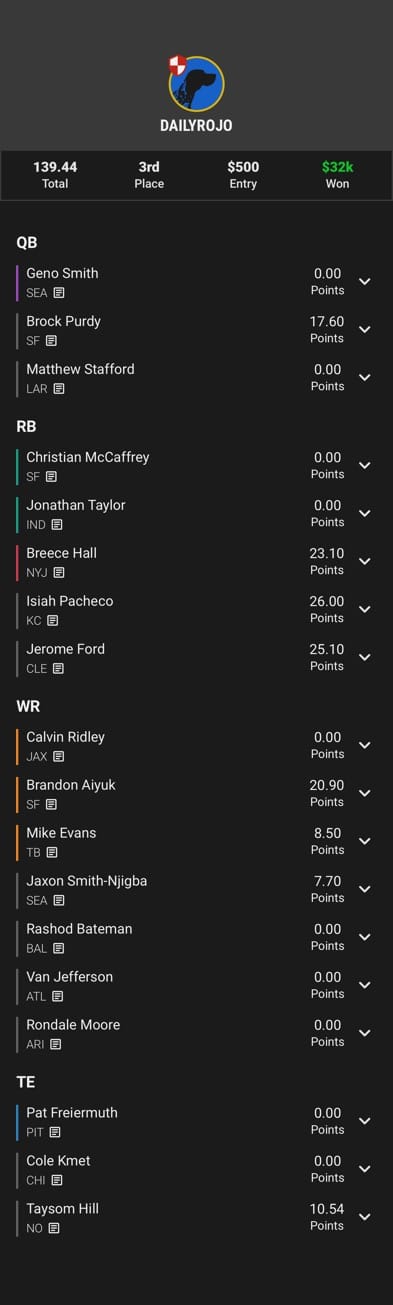

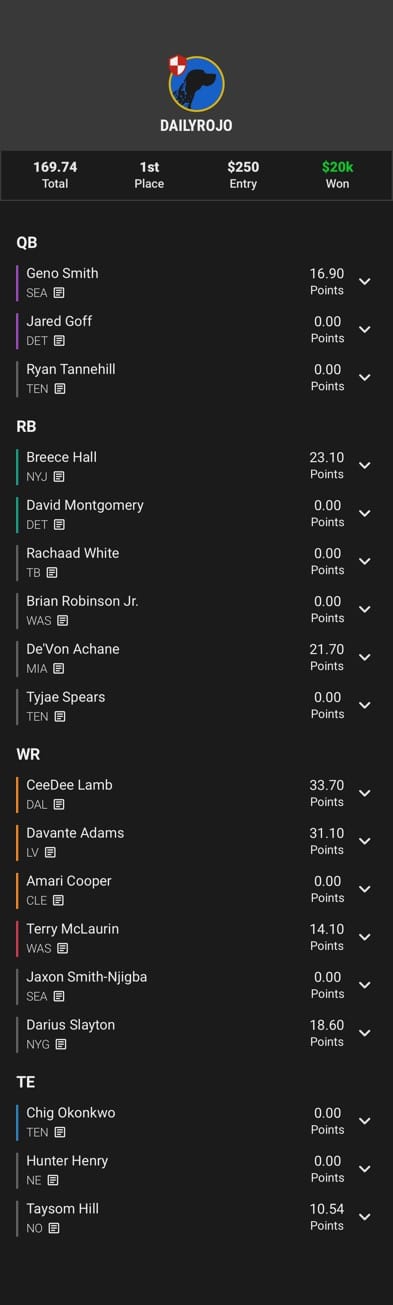

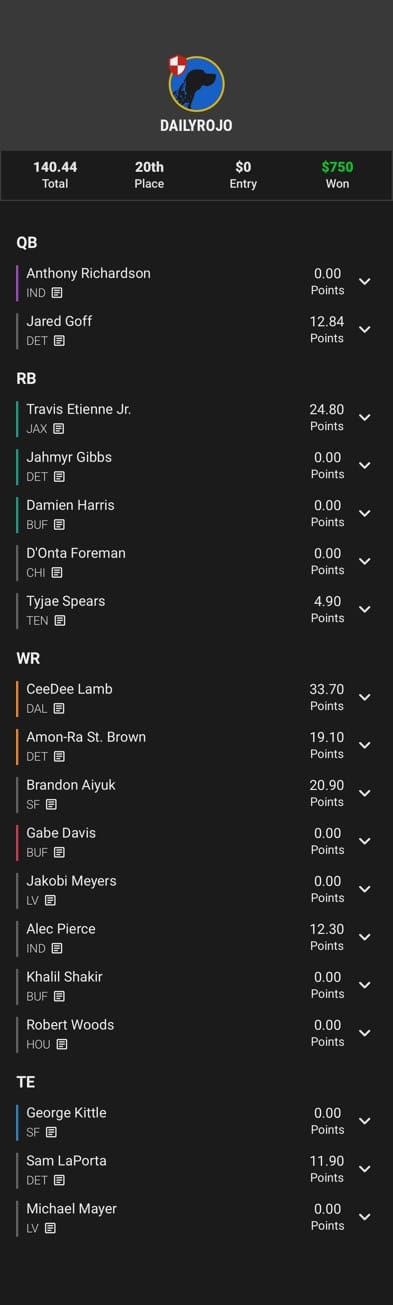

In Best Ball Mania, I took big stands on Breece Hall (37%) and Jaylen Warren (34%). Helpfully, I also mixed both RBs into a variety of builds and structures.

Hall and Warren were my only two players above 27%. And among 150 max drafters, I finished 31st in Sackreligious' Diversification Percentiles (higher being more diversified).

Meaning, that despite those big stands, my overall portfolio was still somewhat diversified.

I was also the least diversified at RB, which is the position where I want to be the pickiest, and in line with my biggest player stands.

Ultimately, I made five finals last season. Breece Hall was on three of the teams, but Warren was only on one.

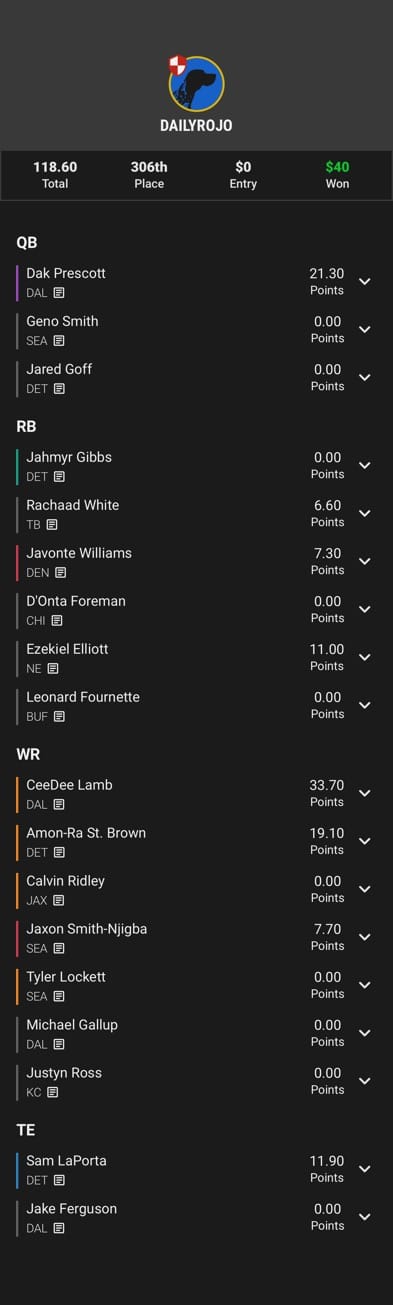

As it happens, 4-of-5 teams had one of:

- CeeDee Lamb

- Jared Goff

- Geno Smith

- Jaxon Smith-Njigba

And 3-of-5 had Amon-Ra St. Brown stacked with Sam LaPorta.

Of these six players, JSN (23%) was the only one who I was more than double the field on. I had minor stands on LaPorta (15%) and Smith (14%), was even on St. Brown (8%) and was actually slightly underweight on Lamb (6%) and Goff (6%).

I'm not saying I got everything right here.

In fact, my point is that I didn't attempt to get everything right.

I took extreme positions on two RBs and a handful of other stands in the 20-27% range. But I spread out some of my other player-level bets, leaning on structure and scenario-based drafting.

Stylistic Flexibility

Sackreligious and I took similar approaches to positional diversification last year, but he had a bit more diversification built in. I finished in the 31st percentile in Jaccard similarity; he finished in the 39th percentile.

Sack's style still allowed for big stands and a concentrated RB pool. But he took a slightly more sensible approach in a highly variant game.

We don't have to stop there.

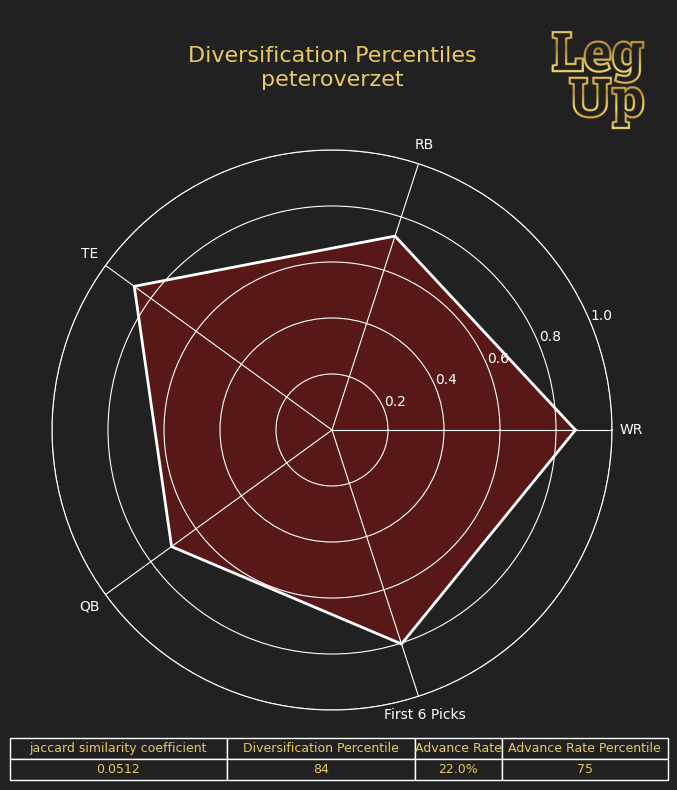

Peter Overzet was a diversification maestro last summer, finishing 84th percentile.

And despite being the original Week 17 bro, Pete finished with a 75th percentile advance rate, easily besting me (45th).

Pete's more diversified approach allowed him to attack from multiple angles—reducing risk while maintaining upside.

Pete's approach clearly demonstrates that if you focus on building the strongest team available in your specific draft room, you can build an awesome portfolio. It's not like Pete didn't have player stands; they were just less aggressive than mine.

If you're into aggressive player stands... cool, me too. But if you see your biggest edge as team construction and navigating draft rooms... push that edge. The naturally diversified portfolio that style generates can be very appealing.

Planning Ahead

Looking forward, do I want my Jaccard percentile to go up or down?

Up.

I'd like to build a more diverse portfolio.

But how much more diverse do I want to get? That partly depends on whether I think I've found another Breece Hall. You already know who I think the next Warren is (it's Warren).

Honestly, I do see some big edges in ADP, and I want to push them. Stylistically, that's the type of drafter I am—what has more legendary upside than correctly identifying The Tree?

But odds are I won't feel as strongly about a player as I did about Hall. Last year, I was screaming that Hall was truly a rare opportunity... and legitimately rare things don't happen every year.

More importantly, even if I do see another Hall, I still want to build a more diversified portfolio than last year. I don't have any regrets about hammering Hall and Warren last year. But I think I tried to get too many things right around them.

This year, I want to be more thoughtful, deliberate, and cost-conscious when building out secondary player stands. I also want to do a better job of admitting when a tie is a tie to avoid creating inadvertent player stands.

In other words, after thorough research confirms a priority player target... I'm not done.

I then need to carefully consider how to set myself up with a diversified portfolio of teams around that target.

If I correctly identify another Tree, I don't want to disproportionately pair the rarest tonewood on earth with Skyy tuners. Instead, I want a diversified portfolio of structures and players around that legendary find, providing a variety of paths to a harmonious finish.

Details on $50 Underdog Credit, 40% off Spike Week, Discord Access, Premium Podcast Feed

Full Newsletter Archive